The infinite paths of other reading led me away from that intention, finding the Eddas inaccessible to my gifted but young mind. As yet unschooled in poetry or archaic language structures found in Dante or Shakespeare, instead I started reading the staples of fantasy -- Tolkien, Leiber, Moorcock -- but still knew at root of all that high adventure, mythology was that genre's foundation, and that base would one day await me when I was ready. And while I was ready decades ago it's only now I've since walked the labyrinth, drank mead in Valhalla, witnessed geneses and apocalypti, and have much to report of unexpected disappointment, ancient wonder, and the revelations of the gods themselves in these first-hand sources.

Enuma Elish

(~7000-1100 BCE)

Possibly the earliest mythology, there's precedent of the flood, a washing away that occurs in many other myth cycles, but may very well be remembered from a flooding of the Tigris and Euphrates, or even Mediterranean tidal waves. The Elish is moreso a Babylonian story of creation and generational change that ends in fire god Marduk's victory over a more primal Tiamat, his grandmother and ancient she-dragon/water-serpent bent on revenge and destruction. Reading of sky-god Anu (Ah-nu) and company feels representational and there's alot of speculative prehistory that speaks of these deities being ancient aliens or advanced astronauts, but if it's really there it's not overtly apparent. We could possibly spend the same amount of millenia guessing what else may have been at play behind these stories, but we may never know short of finding The Tablets of Destiny hidden away somewhere next to a lightning gun and levitation harness.

The Library of Greek Mythology

(~100-200 CE)

Less a storybook and more of a primer, it's like reading a genealogy with addenda interspersed in the family lists. As a reader this was rather disappointing, though it delivered small delights for me from time to time in versions and variants of tales I'd read about before. Historically this document's priceless and lends itself to comparing with other surviving classical works, like the royal dramas of Sophocles and Aeschylus, or the Homeric epics and hymns. The Greek writers and scholars saw no difference between history and mythography. To them, it was the same, sacred as if automatically channeled from a muse, and given the overall consistent structure of the stories it may very well have been.

Prose Edda

(~1200 CE)

The big surprise here is the recontextualization of Norse myths into classical Greek works by stating that the Aesir were descended from the house of Ilium at the beginning of the book(!). Given then-Christianity's recent ascent in Scandinavia one might imagine the author as ruler of Iceland had to cover his hind by couching the Norse beliefs in an already accepted body of ancient religion or otherwise be branded a heretic. Pragmatically he did it to gain favour with the regional rulers in Denmark by adding a genealogy to tie their royal house to the Aesir's lines of descent, granting them a legendary legitimacy and thus cementing his alliances to the Danes by presenting the work. But all this effort in setting down these stories also raises the question if he still believed in the Norse deities. Sturlusson died in a basement, discovered while hiding from his enemies. He was 70, which was quite old for a man in the 13th century. Maybe he had a cane in one hand, but I hope he had a sword in his other when they found him waiting for them, which would be answer enough.

Poetic Edda

(~1200 CE)

This Edda's made up of surviving verse poems, much of which is retold and filled in more completely by the aforementioned Prose Edda.

Odin's "Sayings of the High One" could easily be repackaged for contemporary management and business schools, the same way one reads Sun Tzu's "Art of War" or Musashi's "The Book of Five Rings". The God of Wisdom's advice holds to this day, a timeless counsel for handling negotiations of any sort.

The 19 spells of Odin could have be metaphors for social and leadership skills, but I'd like to think of its runes, magick swords, and elixirs as literal. In our quantum world the truth is that they are both at once.

A scientific rationalization of Ragnarök (the Norse end of the universe) implies that the all-consuming fire of Surt over the Nine Worlds may have been a volcanic cataclysm that happened in Iceland, which would seem a final soot black sunblotting winter and rolling lava fire over nearly everyone and everything on the small island nation.

What's startling is how recently the Codex Regius (the Edda's manuscript) comes to us, only widespread into English in the mid-1800s, possibly on the coattails of the Gothic literary movement with its taste for doom and grim tragedy.

The tragedy seems to be that it isn't inevitable external forces that bring about the end: It's an internal lack of integrity and honour. Over and over the lays (especially in the Sigurd/Völsung/Nibelung cycles where family strife destroys whole kingdoms) show that dishonesty and oath-breaking not only weaken the operational fabric of society but show a decay in the fiber of the world wrought by the gods through compacts and agreements, and when these given words are rendered worthless the resulting existential void proves real and the world seals its own physical destruction.

The Zohar

(~1300 CE)

Not really the occult tour-de-force I'd expected from "The Book of Splendour", or a hidden pre-genesis account, but more of a secretive religious commentary on the Torah. It's insight comes from an edgy exploration of the nature of YHVH, and its emanations from spirit to material as it flows through its ten aspects in the kabbalistic tree of life. These ten Sephiroth are somewhat akin to a pantheon, but are also rungs in the overall ladder to the Ein Sof (the Infinite). The heart of YHVH's divinity is that it needs us to manifest, to actively hold the four-fold meanings of the Torah in our hearts so we may share completeness with our partners, families, and selves to reclaim the illumination that was lost but can be refound through the practice of kabbalah. That sounds rather mamby-pamby but it's really a pretty profound approach to actively connecting to the divine. One could spend a lifetime delving into the workings of this body of knowledge and many scholars throughout the generations have.

Codex Boturini

(~1500 CE)

In the wake of The Conquista, the Spaniards burn the codices, condemning them as books of black magick and idolatry. More significantly they were the repositories of Mesoamerican culture and learning, the myths, academia, astronomy, religious ritual, and histories, and, to finalize their conquest, the Spaniards destroyed them to subordinate the surviving Aztecs and other peoples of the Mexica Empire.

Of the innumerable codices crafted by the scribe class (yes! A whole class of writers from which I'm descended!), a mere 500 (only 15 of these authentically being pre-conquest) survive, the conquest's subordination even now reflected in many of them being named after whichever European's collection they ended up in. The Borturini would more accurately be called "The Migration of the Aztecs", and was probably made during the early Spanish colonial period just after the conquest.

A codex was originally painted on a shredded and pressed sacred fig tree bark paper (called amatl) horizontal scrolls, which were then folded accordion-style and bonded to a top and bottom cover.

The "Migration" is the legendary pictographic history of the Aztecs leaving their lagoon homeland at the behest of their deity Huitzilipotchtli, the hummingbird god of war, whereafter they wandered for 100+ years! One always thinks of the Aztecs being the gloriously ascendant rulers of the central Mexican valley, but here is a tale of faith, separation, ritual, disease, defeat, and perseverance that is truly epic. The unfortunate bit of this story is that on page 23 it ends in a torn page! We obtain the rest of the story from other records, fragments, and ethnographic accounts, but "The Migration" reveals a wandering nation's long quest for hard-earned dominance.

Codex Borgia

(~1500 CE)

This 76 plate codex of stunningly painted panels is at its simplest a 260-day perpetual calendar made of 13-day weeks, with 20-day signs, but if you think of our calendar with its seasons, equinoxes, holidays (holy days), astrological breakdowns, and other annual periods, this codex reveals cycles in the lives of the Aztecs.

This tonalpohualli (book of days/destiny) presents the calendar in repeated forms and fashions, associating the weeks and days by turns with cardinal directions, particular deities, trees, offerings, celestial bodies, or legendary and supernatural events and locations, all interchangeably, compatibly, astrologically and prognosticatorially. And given the accordion form of the codex it can be opened as wide or compressed and tesserated into many different page combinations, adding even more complexity into how it could be read.

While much of the pictography is subject to interpretation, like tarot, tea leaves, dreams and visions, all these permutations not only prescribe ritual for the individual and society, but also actually divine the future. One is named in Aztec culture after the day they where born, and from this one's tonal (soul/spirit/self) is given direction.

Academically, alot of supposition by linguists and anthropologists has been put together in figuring out the Borgia. Odds are that the meanings in these arrangements are for the initiated priests of the particular temple the codex was housed in, and this codex may very well have been a regional or even one-of-a-kind document.

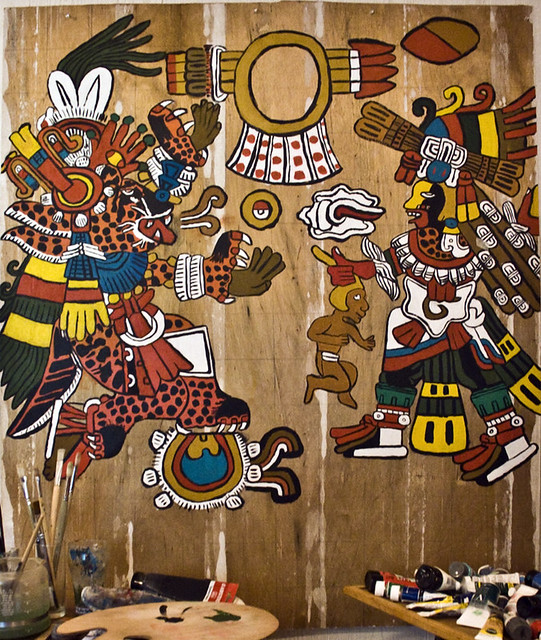

Depicted in bright iconographic colors were the gods and goddesses of the Aztec pantheon: god of games Macuilxochitl, goddess of flowers Xochiquetzal, and the messianic Quetzalquatl, the feathered serpent, who stood for civilization itself.

And like an ancient graphic novel, eight pages host the enigmatic adventures of initiate "Stripe Eye" and the black priest "Smoking Eye" as they cross sacred boundaries, interlope through temple districts, and deal with a curious bag full of supernatural darkness. Also mentioned in a few places is Chalchiuhtotolin, "turkey of the precious stone" (WTF?), along with other compelling and unexplained references.

From this and other sources, the Aztecs lived in a dream of beautiful horror where sacrifice wasn't just representational, it was literal as there are illustrations of bratty children being drowned to make it rain, noble kings piercing their genitals to show they had a pair tough enough to lead, and devout priests cutting hearts out of many, many, many human sacrificial offerings. The universe didn't provide for us, we provided for it -- or the sun didn't rise, the gods turned against us, and the cosmic gears that ran on blood & hearts would just stop. Which begs the question of 2012 ... and the coming of the sixth world. Perhaps Quetzalquatl will return to save us all. Or god of sorcery Tezcatlipoca will show up to save us from him.

|

| [Tezcatlipoca vs Quetzalcoatl. Credit to Patrick Charles.] |

# # #

Addenda from 9/4/2012 response to inclusion of other mythological sources:

Thanks for the praise.

Outside of Budge's pieced together interpretations, there doesn't seem to be much Egyptian source material, plus when one goes to Egypt you find out alot of the stories tend to be socio-political metaphors for Upper versus Lower Nile conflicts and resource squabbles, and more attention's focused on the dynastic legacies of the pharaohs which makes it all much less compelling, but I find their death-centric architecture & design of deities aesthetically wondrous. Just scored a Set statue this week, which is way weird because in Egypt he's really nowhere to be found, except in relief at Abu Simbel.

The Indian Mahabharata, Upanishads, and Vedic literatures just seem to be a daunting & lifetime undertaking. And where even to start such a bottomless body of study? And with whose translations? A girl recently told me a terrific story from Upanishads where a boy, via his father's offhanded dismissal, unintentionally gives his son to Yama, the lord of death. That narrative's totally my flavour of ice cream, but unsure if the overall system speaks to me on an intuitively truthful level, truth being personal and relative, (oooh, big cans of worms there. Yeah.) or it could just be it's just so outside of my cultural bias that I can't wrap myself around it spiritually. Am watching a Bollywood movie featuring re-incarnation as a central plot-point mechanism, so maybe it'll learn me something.

Right now I'm drawn again toward Norse Reconstruction, which I gather you're also curious about with your Odin post. There's some really good podcasts out there where they discuss modern paganism and the ancient lore. Ravencast's done by a well spoken East Coast professional couple who do a nice job of presentation, and Raven Radio's an unedited technical glitchfest but nearly every show there's some great perspective being issued forth from a Kindred in New Mexico with members who have completed all the serious mythology homework and aren't afraid to apply it to the now. They're all about drinking as ritual, too. Got mead?

# # #

While a mostly happy bookstore fixture for over two decades, Guillermo Maytorena IV is currently willing to entertain your serious proposals for employment as a literary/cinema critic, goth journalist, castellan, airship pilot/crewperson, investigative mythologist, or assisting in a craft brewery. Should you be connected to any of the above or equally interesting endeavours, do contact him via LinkedIn or G+.